Avoiding Idle Talk

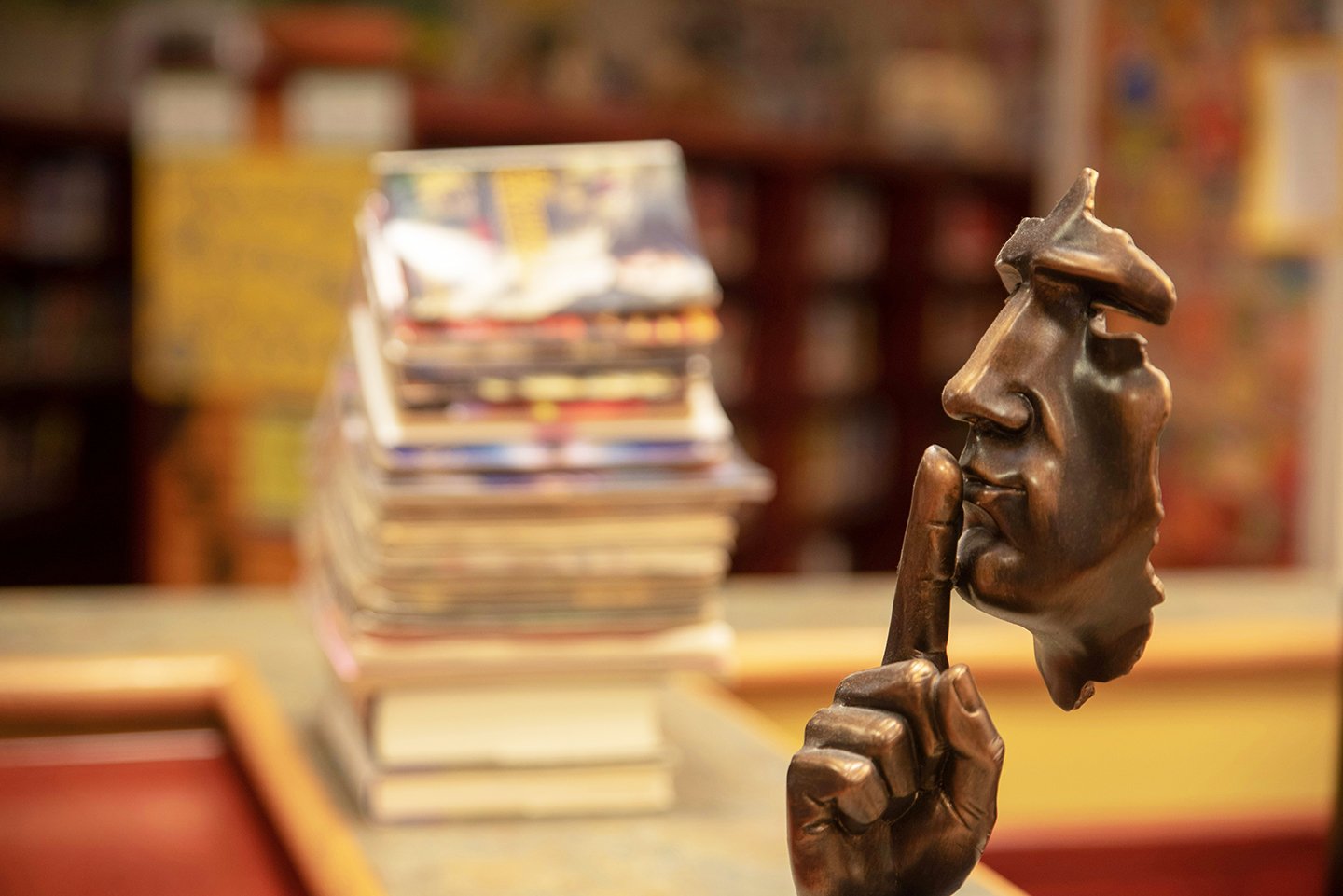

Photo by Ernie A. Stephens

In the seventh talk in a series on the Eight Awarenesses of Enlightened Beings, Zuisei speaks on the eighth awareness: avoiding idle talk (she changed the order of the talks in order to end with wisdom).

Master Dogen said, “To totally know the true form of all things is the same as being without idle talk.” In that complete knowing, there is no room, no opportunity, for idle talk. Knowing the true form of a thing, there is no one to speak about it idly, or to speak about it at all.

Words cannot express the reality. Live words can point to it, but they are not it. And yet, since we have to speak, how do we do so in such a way that we practice abstaining from thought and language that keeps us bound? How do we create space to rest in a deeper sense of knowing and trusting in our innate goodness?

Recorded at Zen Mountain Monastery 07/16/2017

Transcript

This transcript is based on Zuisei's talk notes and may differ slightly from the final talk.

Avoiding Idle Talk

Master Dogen said,

“Having realization and being free from discrimination is what is called avoiding idle talk. To totally know the true form of all things is the same as being without idle talk.”

To totally know the true form of all things is the same as being without idle talk. And avoiding idle talk is the last of the Eight Awarenesses of an enlightened being. And in our school, it's the last teaching of the Buddha. That's it. That's my talk.

It's actually tempting, actually, the way I was feeling this morning, and with this cough I didn't feel confident I could make it through both interview and the talk. So, my apologies for not doing interview—and the scrambled order of these awarenesses. I wanted to save Cultivating Wisdom for sesshin, and Gokhan gave a talk on avoiding idle talk just a few weeks ago. So I'll try not to repeat what he said.

There are many ordinary forms of idle talk that we all engage in and can recognize. This is talk that has no other purpose but to elevate, to distract, to disparage, to compare. Even St. Benedict, in his Rule of St. Benedict, recognized the danger of idle talk and built a safeguard.

He said, “Above all, one or two seniors must surely be deputed to make the rounds of the monastery while the brothers are reading. Their duty is to see that no brother is so assiduous as to waste time or engage in idle talk to the neglect of his reading, so not harm himself, but also distract others.” And Benedictines in general are wary of idleness. They, like us, work a lot. Their motto is ora et labora, pray and work. But one sister changed it to ora et laborara, e labora, e labora. Some of our residents would probably say the same.

There's talk whose purpose is, as I said, just to distract or to create a kind of buffer between you and me. But I would also argue that there is a kind of idle talk that can bring us closer. I've seen people, women especially, who do it well. They'll praise another woman's perfume or a piece of clothing or ask for a recipe. And if the purpose is not to ingratiate, but if it's done out of a true sense to come closer, to connect to the person that you have in front of you, it works. In a setting like this, we’re often meeting people we don't know, or people we don't know well. But this kind of chitchat reminds us that fundamentally we're the same, right? We're human beings. And life is scary, or it can be. So why don't we just meet on this safe ground and see where that takes us? Maybe, in that sense, it's not exactly idle talk, but it's not deep either. It's ice-breaking talk.

We're getting ready to do a family retreat next week, and I was just thinking about the kids and how we do a bit of this kind of ice-breaking, because the groups that we have, they only come once a month. And so we have them for three hours, and then the next month, it may be the same group, but it's often not. And so there's a little bit of bringing the group together that we do each time we meet. We have a name game that we do, and sometimes it works very well. Sometimes you can tell where it just kind of leaves them cold. There was one that was,—I don't know if it was the most successful, but it's certainly the one that I remember the most, where you had to say your name and your favorite injury, a scar that you had somewhere on your body. They really got into it! At a certain point,we had to stop it because the parents started to get into concussions. So we cut it at the pass. But it's this kind of low-level or high-level talk that just has that purpose, just to make us a little more comfortable. And then there is talk that is just idle, period.

I've told some of you the story when I was 16, me and my best friend went off to the beach together. There was a group of five of us, actually, five girlfriends, but their parents were not as progressive as ours, so they didn't let the others go. But they let me and my best friend go, and mostly, they had no reason to distrust us. So we went. It was a time when you could actually do that in Mexico. I wouldn't do that now. I wouldn't travel alone, pretty much anywhere, really. But then it was okay. So we went, and we went out to a couple of clubs. One night I was feeling playful, which happens so rarely that when it does, I take the opportunity. I looked across the room, and not too far away, there was a guy talking to another guy, and he was introducing himself. And I read his lips. And so I knew that his name was Alberto. So I said to my friend, “watch this,” and I went over. I went over to Alberto, and I gave this big shout.

“Alberto! How are you?” I gave him a hug and I kissed him on the cheek. “How’ve you been? It's so nice to see you again!” And he's looking at me, and I can see the wheels turning: Who is she? Who is she? I'm like, don't you remember? We went to such and such, and I named another well-known club on another beach. I saw you last year. Don't you remember?” He's like, Yeah! We talked for about half an hour. I walked away. He had no idea. He’d never seen me in his life. It was completely, completely idle. But harmless, I think.

There's talk that is silent or voiced. There's talk that disturbs and agitates the mind, the Buddha said, and it can be talk that is outward-oriented, but it's very often not. It's very often us talking to ourselves. And there's talk that keeps us from seeing the true nature of things. This is what Master Dogen said. In one sense, that's the most pernicious kind of talk, and it's what I wanted to focus on. He just says it directly: to totally know the true form of all things is the same as being without idle talk. Now he's speaking of another level. In that complete knowing, there's no room, there's no opportunity for idle talk. In knowing the true form of a thing, there's no one to speak about it idly. There's no one to speak about it at all.

One of my favorite stories in the Zen literature is that of—it's a story about Zhaozhou's cypress tree. A monastic asks Master Zhaozhou, “What is the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming to the West?” which really is a way of asking, What is Zen? What is the fundamental nature of things? And Zhaozhou says, “The cypress tree in the garden.” The student says, “Don't teach me using things.” Why are you pointing to the concrete to express the ineffable? And Master Zhaozhou says, “I'm not teaching using things or using objects.” The monk asks again, “What is the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming from the West?” And Zhaozhou says, “The cypress tree in the garden.”

About 200 years later, a monk is sitting, he's traveling, he's going on pilgrimage, and he's sitting with this koan unremittingly. And I've always imagined him wrapped up in a thick woolen robe, and he's at an inn, at a roadside inn, and it's winter. I imagine the snow piled up against the walls of the inn, and it's so cold in his room that you could see, if you could stand there, his breath going in and out. And he sits like this, and because it's snowing, it's completely, completely silent. That very particular kind of silence of winter. He sits like this with complete concentration, every cell in his body, every thought of his mind on Zhaozhou's cypress tree. He goes one day, and then it turns into night, and then it turns into day again, and he's still not moving from his seat. Soft footsteps approach the door, and then they retreat again. And as the sun starts to come very slowly up the mountain, he's still sitting. He doesn't see the sun. More and more, his mind is that that tree, roots going deep into the ground, branches reaching up to the sky, that last remnant of the moon.

Now it's the second night, and a thief slips in through the window into his room. Because it's dark, he doesn't see anybody else. And he's maybe rustling through things. And all of a sudden, he turns, and the light of the moon shines through the window. And the thief is scared half out of his wits, because the only thing that he sees is this enormous cypress tree sitting in the middle of the room.

In Buddhism, the dharmakaya, the body of reality, is one of the three bodies of the Buddha—the body of truth. It has no limits. It has no boundaries, no characteristics, no form. And therefore, it manifests the true form of the Buddha and of all things. It can manifest as a cypress tree, can manifest as a lawnmower, as a pot of chicken soup, as you and me. And Trungpa Rinpoche says, in tantric terms, the dharmakaya is vajradhatu, indestructible space, or dharmadhatu, the realm of thusness. All the names and laws can function within it and not be conditioned by it.

Because, in an earlier passage he said that the word dharmakaya is conditioned. You have to speak. In a sense, it's like the Buddha has to take form, conditioned form, and then there has to be a conditioned name. But all the names and all the things and laws that happen within it are not conditioned. And in order to experience it, you have to undo old experiences. So when the old experiences cease to function, are non-existent, that's the kind of thing it is, because the ground has no allegiance to anything. When the old experiences cease to function, you can be a cypress tree. You can be a stick of incense. You can be a mat. You can be a bridge. You can be a mountain. And we could also say that when the old experiences cease to function, the ground has allegiance to everything without distinction.

That cypress tree is pledged to the soil that it stands on, and the wintry sky, and the passing clouds, and the waning moon, the cold night air, and the monastic sitting unmoving. It is in allegiance with all of these things, and is therefore inseparable from them.

The Trikaya is the three bodies of the Buddha. And the second one is the sambhogakaya, which is the reward body, the body of bliss. And then the nirmanakaya, which is the manifestation body.

When the old experiences cease to function, you can be a cypress tree. You can be a bridge.

Because he's speaking from a Vajrayana perspective, these bodies are in relationship to a fierce deity, Vajrayogini. In Tibetan Buddhism, both the emptiness and the potentiality—so what can arise and function out of that emptiness of shunyata—are embodied in the form of a dakini, a female spirit called a sky-goer. Vajrayogini is both a dakini of great power and a female Buddha. She is also said to be the fundamental essence of all the buddhas, including these three bodies. The dharmakaya is the absolute primordial mind or its basic spaciousness. It is this ground that has no allegiance or has nothing but allegiance. It is also, more simply, mind and thoughts. The Sambhogakaya is the emotional and energetic body. It manifests as concepts and as speech. And the Nirmanakaya is the physical body. It is form, it is action. It is also the manifestation of all the buddhas who have ever lived. Shakyamuni Buddha is the historical manifestation of that primordial Buddha. Vajrayogini, in her fierce, even frightening manifestation, encompasses these three bodies. And of course, we could ask, well, what does this have to do with me? What does it have to do with the fact that I suffer ? What does it have to do with my partner leaving me, or my child getting sick, or my job being taken away, my life catching fire? How does seeing the true form of things help me? That's not an idle question.

There’s that story of Dongshan standing in a room very much like this one, and he's doing service. He's chanting along to the Heart Sutra and he's saying, there's no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind, just as all of us chanted this morning. Suddenly, he stops and says, well, wait a second. I have eyes. I have ears. I have a nose. I have a mouth. Why is the Heart Sutra saying this? Why do all the schools of Buddhism chant the Heart Sutra every day? What is this? That's the kind of inquiry we want to do.

What does this have to do with me? What does this have to do with my life? Why have teachers for millennia spoken in all these different ways? Sometimes ways that seem very direct and very practical, perhaps very relevant to my everyday life. Somebody asks Zhaozhou what is the nature of Zen? And he says, “Have a cup of tea.” We get that. It's all about being completely present in the moment with this cup of tea, the taste in my mouth. We sort of get it. But what about those three bodies of the Buddha being in that cup of tea? How does not just knowing that—certainly not knowing intellectually—but also realizing it at some point, help you? How does that transform your life? Does it? That's really the question.

Those of you who did the yoga retreat yesterday with Barbara, I hope you have some sense that our emotional body, our physical body, our psychological body, our spiritual body, our mental body, our breath body—all of them need to come into alignment. When they don't, when they're not, we feel it. It manifests perhaps as illness, or it manifests as unease, or it manifests as confusion, manifests as suffering. When our understanding is cloudy, our actions can be haphazard, our speech is equivocating at best, or divisive at worst. Patanjali called asana a firm, stable, relaxed, and comfortable posture. This refers directly to the seated posture, which was how yoga began, but you can extend it to all the postures. Of course, we won't be comfortable until we really understand ourselves. I won't be comfortable until I understand you to the best of my ability. And so we really don't need to know a thing about these three bodies of the Buddha, but we need to know everything about this body. That's the only way that we will have realization and be free from discrimination, as Master Dogen says. Without being clear about this, we can’t be clear about that. And our world is a perfect example.

It seems that the more we know , the less we really understand. Therefore, our struggle as individuals, as a country, as a species. But it doesn't have to be like this. That's the Buddha's third noble truth. It doesn't have to be a struggle.

I had a bit of time to myself in these last few days. A bit of time to be with this body. And normally, when I feel sick, my experience just narrows drastically. And, that still happens. At some point, when I'm sick, invariably I feel sorry for myself. Actually, let me be kinder. At some point, I just feel my vulnerability—I feel what a fragile, vulnerable proposition it is to be a human being. Luckily, I haven't yet had any serious illness. But I get sick, unfortunately, frequently enough to know that the balance is quite delicate. So, I was feeling that., but also that my illness, my aging, my death are really just a dot in that sea of existence in which all manner of bodies are growing old or dying.

I ate a banana that was slowly turning, oxidizing, dying. The bacteria in my body that I was working so hard to expel, were hopefully also dying by the millions. The hydrangeas in our yard that look so alive, so full of life, in the fall, would start to decay, would eventually die, and hopefully be reborn again in the spring. And it was comforting. It was deeply comforting to feel myself a strand of this web, to feel a part of this body of reality that does not grow ill or die. My own sickness would change, and it would pass, or it would not pass. Either way, I was not and had never been apart from this web. I also realized how much I don't know about this body and this mind. There's what I think I know and what I have slowly, slowly learned. But that is really still so much, the tip of the iceberg.

I was reminded me of that John Powell video that the residents watched recently for our Beyond Fear of Differences work. Powell is a professor of law in African American and Ethnic Studies at Berkeley, and he does a lot of work around racism, but also understanding bias, and understanding its neurological basis. He was saying that basically our unconscious functions on the basis of bias. It doesn't matter whether we think we're good people or not.All of us are biased. Our unconscious processes 11 million bytes of information per second. Eleven million bytes. But our conscious mind can only process 40. So basically, that means that we’re like a driverless car that just got the instructions punched in by a whole group of people—nothing to do with us. And you can't tell yourself, well, I'm just not going to be biased.

Imagine that your brain is a bridge designed to hold 40 cars per second, and 11 million cars show up. You're going to have a traffic jam that will last hundreds of years. But you can't shut down the bridge either. So we have no choice but to let some cars through and not others. In other words, our unconscious is really driving most of our actions. He calls this implicit bias or implicit social cognition, and it is activated in us involuntarily. That's why we can’t sayI just won't be biased. We have to have a way to sort through all this information, and that very much depends on the society that we live in, on the norms, and then the biases that we've created over hundreds of years, sometimes millennia, about what it means to be male or female, white or black, big or small, this or that religion. Talk about idle talk—except it's not really idle, because it can manifest in very hurtful ways.

That’s why we have to work as communities he says, to change the stories, the meanings behind our biases. It’s not enough to do so at the individual level. But this is an idea we should be comfortable with, given our bodhisattva path. I can’t realize myself alone. And not only that, I can’t affect how you will perceive that manifested buddha body alone either, whether you’ll see it actually as a buddha or a demon. I can't realize myself without you. I need you to help me to see what I cannot see.

There was a professor at Stanford who was doing tests about priming, basically these experiments. He had a group of all women who were going to take a math test, and he had two groups with exactly the same level of experience. One group just took the test, did well. The other group, the test group, he said, right before they took the test, “I so enjoy teaching here at Stanford because there are so many smart women.” They took the test, they did terribly. The reason is that women, we believe and we're told, women aren't good in math. And so when he primed the salient characteristic: female, something happened got activated in the women's unconscious mind, and they did terribly. Next he repeated the experiment, and he said, I really love teaching here at Stanford because there are so many smart Asian women. And they aced the test.

I can't realize myself without you. I need you to help me to see what I cannot see.

The salient stereotype, in this case, is that Asians do very well in math. And so that got activated. This kind of experiment has been replicated over and over again. So, think of the four immeasurables as a kind of priming, a skillful priming. The very opposite of idle talk.

May you be filled with happiness and know the root of happiness.

May you be free of suffering and know the root of suffering.

The first two. So when I am doing that, I am saying, I wish you happiness, loving-kindness, compassion, joy, equanimity.

When I wish you happiness and freedom from suffering and joy and equanimity, I’m saying I see you as a human being who deserves these things

I’m looking beyond what someone else might call your worth and I’m saying “Because you’re alive, you deserve these things.” You don’t need to prove your worth any further. Your actions may need some work, but your fundamental worth is not in question. That is seeing the true form of things. That is not separating myself from or elevating myself over you.

Think of the Karaniya Metta Sutta as a kind of priming. Chanting it every day, you’re saying I want to be a person skilled in goodness. You’re reminding yourself that this is your true nature and you’re invoking its reality so that when the time comes, you may act accordingly.

Think of Sengcan’s: In this world of Suchness there is neither self nor other-than-self. To come directly into harmony with this reality , just simply say when doubt arises, “not two.”

When doubt arises, simply say “not two.” Simply say, “I am not this, this is not mine, this is not myself.” Think of the Buddha’s instructions on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness: When you’re caught, when you’re really tangled in a feeling of anger, of self-pity, of anxiety or fear, say to yourself: “An unpleasant feeling has arisen in me,” and watch what happens to it.

Your fundamental worth is not in question.

There is a song of praise for Vajrayogini, and the end of it goes like this:

Eternally brilliant, utterly empty,

Vajra dancer, mother of all,

I bow to you.

The essence of all sentient beings lives as Vajrayogini.

From the milk ocean of her blessing

Good butter is churned

Which worthy ones receive as glory.

May everyone eternally enjoy

The lotus garden of the Coemergent Mother.

Our essence lives as the form of this great enlightened mother, this sky-goer, fierce as fire, soft as butter when needed, both male and female, or neither male nor female, blessed and blessing all the worthy ones—that is, all of us.

And this non-thought, unconditioned wisdom, this absolute dharmadhatu, is our home. Or rather, our birthplace. It's where we come from, it's where we return to when we stop talking. It's what we experience when we have the courage to be still. Truly, truly still. Because it does take courage to see and accept our awakened nature. Many, having caught a glimpse, have turned away from it. So it takes courage and humility to accept our greatness. And I mean great as in vast, as in immeasurable, as in limitless, unfathomable. But if we can accept it, even a little bit, then we can live and act as the true persons of the way that we are.

Avoiding Idle Talk, a dharma talk by Zen Buddhist teacher Zuisei Goddard. Audio podcast and transcript available.

Explore further

01 : Eight Means to Enlightenment by Master Dogen

02: Guide to Dakini Land (book on Vajrayogini)