An Amazement: Practicing with Climate Change

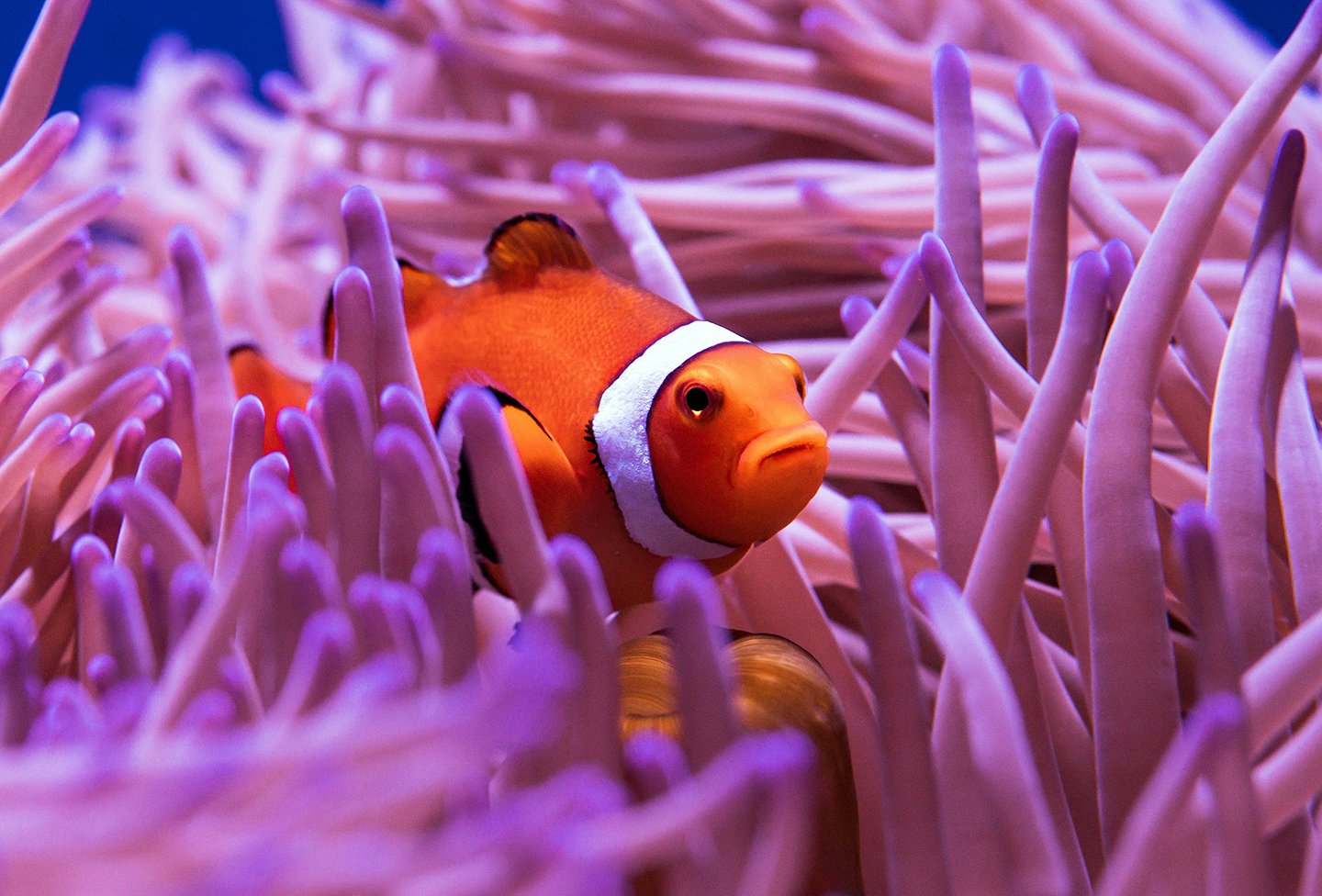

Photo by David Clode

Buddhist practice is the work of cultivating careful attention and amazement. When we see clearly, we reveal the sacredness of the world we inhabit and we see what is needed to care for it.

In this talk, Zuisei delves into the Buddhist practitioner’s essential approach to climate change—practical, sustainable, and inspired by awe. She draws on the work of the poet Mary Oliver, Theravadan Buddhist monk Thanissaro Bikkhu, philosopher and historian Mircea Eliade, and more.

This talk was given by Zuisei Goddard. See below for transcript.

Transcript

This transcript is based on Zuisei's talk notes and may differ slightly from the final talk.

An Amazement: Practicing with Climate Change

Here is an amazement—once I was twenty years old and in

every motion of my body there was a delicious ease,

and in every motion of the green earth there was

a hint of paradise,

and now I am sixty years old, and it is the same.

Above the modest house and the palace—the same darkness.

Above the evil man and the just, the same stars.

Above the child who will recover and the child who will

not recover, the same energies roll forward,

from one tragedy to the next and from one foolishness to the next.

I bow down.

Many years ago, maybe a decade, a decade and a half, I was at the monastery one evening. I’d gone into the women’s locker room looking for something, I don’t remember what, I rushed back there. Without thinking, I jumped up on the bench set up against the far wall and reached up to grab whatever it was from the ledge in front of the window. As I came down, I felt an amazement. I thought to myself, One day I won’t be able to jump up like this, so unthinkingly. I won’t be able to jump up at all. But now I can. I felt both sad and gladdened. I felt sad because it was true, one day my body would not respond like I wanted it to. I had relied on it for so long and so enthusiastically, that in that moment I felt very keenly that future loss. But I was also glad because I could still jump, I could reach without fear, without any concern that any part of me might not work the way it needed to. I could do so many things, in fact, I could run, I could bend, I could bow, I could carry a fair load, and all of it felt easy and so I thought, as Mary Oliver does in this poem (“Am I Not Among The Early Risers”), how amazing it was that my body worked so well and so consistently. Despite the many little illnesses and injuries I often had, it worked perfectly.

Just like the earth, the beautiful piece of ground that I called home and that also held me, and those I loved, perfectly. It still does, the earth holds us perfectly, and they still do, our bodies carry us forward, maybe a little more slowly, maybe not so surely or smoothly, but still. That is an amazement, or it should be, if we’re looking close, if we’re living wakefully. But then, what of the body in pain? What of the sluggish mind that won’t settle, won’t stay on any one thing for more than a couple of seconds at a time? What of the heating earth and the drying rivers and all the various nooks and crannies of the planet that are now filled with tiny bits of plastic, so tiny it’s impossible to see and yet every day we eat them, and breathe them, and drink them, at the rate of roughly a credit card a week. That’s four credit cards a month going into our bodies, and we have no idea yet what this is doing to us, though I can’t imagine it’s in any way good.

So what of all the plastic? What of the fires and the earthquakes and the floods and the droughts and the hot spells? What of the body of the earth that seems to be in the middle of a long burnout? Because it is a literal burnout, in which we find ourselves, isn’t it? This is the writer Katherine May in her book called Enchantment: “Burnout comes when you spend too long ignoring your own needs. It is an incremental sickening that builds from exhaustion upon exhaustion, overwhelm upon overwhelm.“

The term “overwhelm” comes from a mid-14th century word, overwhelmen, which means “to turn upside down, overthrow, knock over” and later takes on the connotation of being completely submerged as if by a wave. Who has not felt that at some point in their lives? I was telling someone earlier in the week that I used to get easily overwhelmed when I lived at the monastery. Which says something either about my capacity or about the amount of work that we had, or both. I’d always have more work than time to do it in, more company than solitude, more conversation than silence. These were just the circumstances, but in my desperation, I’d often pile on more fuel on the fire. I’d come up with more things to fret about just like the story of the student who stepped in a puddle as she was waiting and waiting in the rain for her husband to pick her up. If I’m going to suffer, let me do it right! My partner at the time made me a drawing with the phrase “no pile” inside a prohibition sign (the red circle with a diagonal across it). She put it on my desk, so every time I started to overwhelm myself, I’d be reminded that a good deal of it, I was creating, and I could stop—just like suffering.

Another etymological tidbit: the word stress didn’t take on a psychological meaning until 1955. Before that, it meant “physical strain on a material object,” but mid-twentieth century, the word started to mean psychological distress, and from there it took off. If you look at the graph of usage, it’s escalating and right now, it’s peaking. Our burnout comes from ever-growing stress, the strain that we place or that is placed on us—exhaustion upon exhaustion, overwhelm upon overwhelm.

Thanissaro Bikkhu, an American Theravadan monk and well-known translator and commentator of the sutras, translates dukkha as "stress" instead of "suffering." He says he prefers it because it has many subtle levels of meaning that the word suffering misses. On the downside, he points out, it’s a little too mild to “convey the more blatant and overwhelming forms that dukkha can take.” As a solution, he often uses both, referring to “stress and suffering.”

Briefly, let’s review the three types of suffering that Buddhism identifies:

There’s the suffering of suffering (duḥkha duḥkhata): the suffering that comes just from being born—the pain of birth, old age, sickness, and death. “That which is painful when arising, painful when remaining, and pleasant when it fades.”

There’s the suffering of change (vipariṇāma duḥkhata): the suffering that comes from impermanence. “That which is pleasant when arising, pleasant when remaining, but painful when it fades.”

And there’s all-pervasive suffering (saṃskāra duḥkha): the general anxiety and distress that colors even our happiest moments because we sense, we know, we’re not really standing on solid ground. “That which is not apparent when it arises, when it remains, or when it fades, but is still the cause of suffering.” This is the hardest one to grok. We think, I’m fine, things are fine, I’m happy, I’m safe, then why do I feel this way? Why can’t I rest?

And so, here we are, looking for and hopefully finding a way to rest deeply. Some of you may know that Zen Mountain Monastery is hosting discussion groups around an environmental initiative called The Week. I started watching the films because I’d like to share them with you, and I wanted to get a sense of what that would entail. The reason I’d like us to do this as a sangha is that I don’t believe we can take our bodhisattva vows seriously without engaging in some form of work to heal the burnout, the overwhelm we’ve put on the earth. Maybe, as you hear me say this, you think, Oh no, I don’t want to do this. I’m just barely getting through my days; I can’t take on anything else. The problem is that this isn’t something else. It is the this that we’re living in, and maybe right now we’re still fortunate enough to not have been hit by a major earthquake or fire or flood, but there’s nothing that says that we won’t. The heatwave, we were all affected by it this summer. There’s no place else where this isn’t happening, where we can go to be safe from what we have to reckon with if we’re to go on having a space and a time to talk about dharma or anything else. Without a planet, everything else becomes irrelevant.

What happens inside, happens outside. Our teachings say as much. If we slow down and look close, we’ll see as much and, although the challenge is large, we’re capable of meeting it largely, each of us in our own way, in our sphere of goodness, in our buddha field. I also think it’s very important that as we do so, we keep our sense of amazement. It’s important that we don’t get lost in the dross of our everyday, that we not let our overwhelm tell us we can’t do what needs to be done. That said, you don’t have to do this. I hope that, like ango, you’ll want to, because you want to be in and of your life. Let me figure out how we’ll do this, the logistics of it, and I’ll get back to you with a plan.

Mircea Eliade, the philosopher and religious historian, created the term hierophany to describe the embodiment of the sacred in the most ordinary things. For example, sunlight sparkling on the surface of the ocean, a particular tree felt to be a guardian or a companion, a small wafer made of flour and water but experienced, at least by some people, as the body of Christ. But there’s nothing magical about hierophanies. It’s not that a wafer is ordinary and becomes sacred through the Eucharist. It’s that through our own attitude of reverence, we bring to light what was always there. That’s what hierophany means: to bring to light, to reveal, the sacred or holy. That’s why my teacher Daido Roshi would speak of liturgy as “making visible the invisible.” It’s there, we just don’t see it, but through ritual, through careful attention, we reveal the sacredness of the world we already inhabit. This, to me, is the best way to work with the problems that we face, or rather, that this is what we, as spiritual practitioners, can bring to the table: to remind ourselves and to remind others that this world is sacred, that we are sacred, and therefore we have a responsibility to care for all of it this way.

If you choose to not eat meat, for example, you do it, not because it’s good for your health or good for the environment, although it is on both counts, but because animals, being the sacred creatures that they are, deserve to have a good life, just as we do. We have to eat, of course, but how and at what cost? Several of you have expressed to me your genuine desire to study the precepts and to really bring them into your lives. Well, here it is, your chance. It can’t be abstract. It can’t be what someone else tells you to do. It can’t be based on what’s good for you, or what’s noble, or “right.” If it’s going to work, it has to be based on your ever-growing understanding of how things are, what they are, why they’re integrally connected to you and to everyone else. This is what’s exciting about the precepts. You have to bring them to life in your life, your life, your circumstances. Not the Buddha, not the sutras, not any amount of study will tell you how to step forward. You have to figure it out.

Then again, you don’t have to do it alone, because we have each other, and that is also an amazement.

Here is an amazement—once I was twenty years old and in

every motion of my body there was a delicious ease,

and in every motion of the green earth there was

a hint of paradise,

and now I am sixty years old, and it is the same.

Above the modest house and the palace—the same darkness.

Above the evil man and the just, the same stars.

Above the child who will recover and the child who will

not recover, the same energies roll forward,

from one tragedy to the next and from one foolishness to the next.

We share the same sky, the same darkness, and the same light. It’s because of that fact, that this can actually work, that we can work together and turn things around for ourselves and the earth. The same energies roll forward from one tragedy to the next, from one foolishness to another. But they also roll through every instance of cooperation and every act of kindness and every show of wisdom. It’s not just that the same stars are above the evil man and above each one of us, the same stars are inside. The same stars are inside every single thing, every single being, and when we show that, we become a hierophany. We become the embodiment of the sacred in the ordinary, which is always, always extraordinary. We become, ourselves, an amazement.

And we bow down.

An Amazement: Practicing with Climate Change, a dharma talk by Zen Buddhist teacher Zuisei Goddard. Audio podcast, video, and transcript available.

Explore further

01 : Bringing the Sacred to Life (pdf) by John Daido Loori Roshi

02 : The Dukkha Sutta: Stress translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

03 : Am I Not Among The Early Risers by Mary Oliver