Eight Conditions for Wisdom

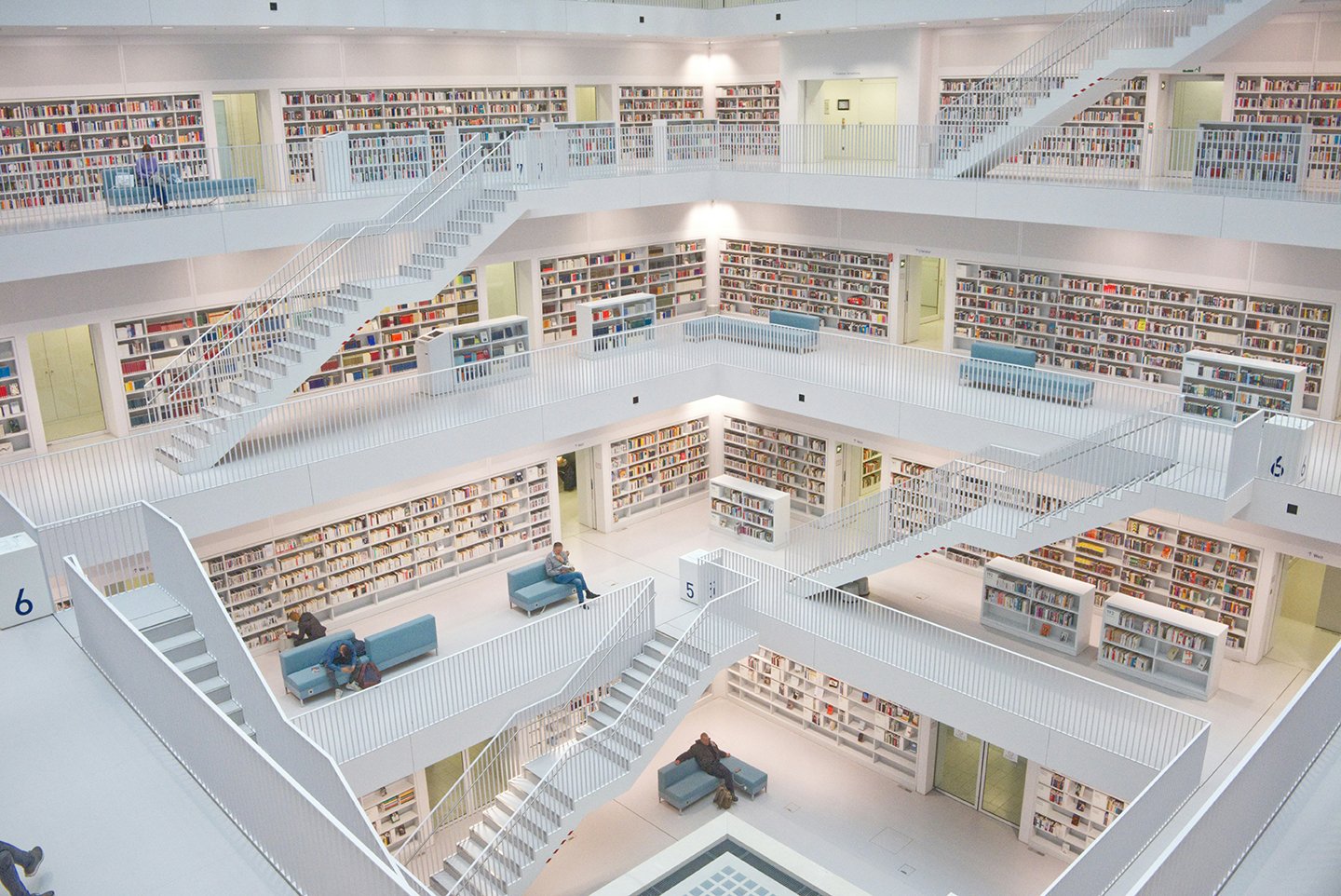

Photo by Niklas Ohlrogge

Zuisei speaks on the Buddha’s Eight Conditions for Wisdom: studying, asking, withdrawal, ethical conduct, learning and reflecting on the teachings, energy, right speech, and understanding the rise and fall of the five aggregates.

These eight conditions give us the ability to see things more clearly and allow us to cultivate the space to hold the knowing of our inherent goodness. Through cultivating wisdom, we are able to accept where we are with more grace and love.

This talk was given by Zuisei Goddard.

Transcript

This transcript is based on Zuisei's talk notes and may differ slightly from the final talk.

Eight Conditions for Wisdom

The bud

stands for all things,

even for those things that don’t flower,

for everything flowers, from within, of self-blessing;

though sometimes it is necessary

to reteach a thing its loveliness,

to put a hand on its brow

of the flower

and retell it in words and in touch

it is lovely

until it flowers again from within, of self-blessing;

as Saint Francis

put his hand on the creased forehead

of the sow, and told her in words and in touch

blessings of earth on the sow, and the sow

began remembering all down her thick length,

from the earthen snout all the way

through the fodder and slops to the spiritual curl of the tail,

from the hard spininess spiked out from the spine

down through the great broken heart

to the sheer blue milken dreaminess spurting and shuddering

from the fourteen teats into the fourteen mouths sucking and blowing beneath them:

the long, perfect loveliness of sow.

Good morning, welcome to Fire Lotus Temple, those of you who are joining us for the first time. It is very good to be here with you in this late winter day as we here and at the Monastery move into our spring ango intensive training period. I know you’ll do ango opening next week here with Hojin Sensei and Hogen Sensei. That’s what’s happening up at the Monastery this morning—our official entering into peaceful dwelling.

Now, this poem that I just read is by Galway Kinnell, American poet, who died in 2014. A student told me and the Lgbtq group about it some time last year or the year before and I was thinking as I read it again recently and decided to use it for this talk, that I myself have started to use the word “lovely” to describe something as lovely. Something I would never have done ten or even five years ago. Maybe it’s because I am now officially middle aged…

There’s a Mexican stand-up comedian, and she says, “How long do I have till middle age? How long till I start teasing my hair and dancing everything like the cha cha?” Pop, rave, salsa, country, hip-hop—doesn’t matter, middle-aged women dance it all like its cha cha. I don’t think I’m quite there yet, certainly not the hair, so there’s hope for me.

And still, I’ve started to use this word “lovely” myself and it made me think of a concern that a couple of people brought up recently and that is that Zen is becoming “feminized.”

It was two gentlemen who were concerned, and maybe there’s others. And I have to admit that I don’t exactly know what the concern is, but there was clearly a negative connotation. One of them said we were sounding kind of “woo woo.” Maybe too soft, maybe too much emphasis on the heart and on love and kindness. Maybe the concern is that we would lose our rigor, our seriousness? And of course, the question could arise, why do we assume that softness is a bad thing? What is the danger of allowing our practice to be softer, warmer?

Zen does have a reputation of being very strict and in less favorable terms, macho. We have a lot of young men coming to the monastery who’ve listened to Alan Watts and who want to cut off their arms like Huike and stand in the snow to prove they’re serious about their practice. Well… that’s nice but unnecessary. Keep your arm and open your heart and mind, then you can help someone.

One of the most helpful pieces of practice advice I’ve ever gotten was from Hogen Sensei, who at the time was Dir. of Operations at Dharma Communications. And we worked together and I was listening to him say the same thing for the hundredth time to someone or other and I said, “Aren’t you tired of repeating yourself? Of saying the same thing? (little did I know I would soon be repeating myself) and he just looked at me and said, “Zuisei, you have to love them.”

Ohhhh…. No, I don’t think so. I resisted that particular piece of advice for a long time, until I saw he was right. Mind you, he didn’t say you have to like them or agree them, just love them. Which to me is the same as regard them, respect them for who they are.

The only reason we have to re-teach a thing its loveliness is because we forget, because we stop seeing and regarding ourselves and one another. It’s not because we stop being lovely in our self-blessing, in our perfection. It’s because that loveliness gets covered over with a lot of words, a lot of thoughts, a lot of meaning we ascribe to those thoughts, and slowly, we lose touch with our true nature.

But just so it’s clear, I’m not saying all actions are lovely. I’m not saying there is no harm, no hatred in the world, of course there is. We just have to look at the news to know the world is not always lovely. What I am saying is that we create that harm, that hatred. Left to themselves, things, beings, tend towards goodness, towards harmony.

Pema Chodron tells the story of an irate man confronting Trungpa Rinpoche on this and saying, “How can you possibly say that? Human beings are inherently flawed.” And Trungpa Rinpoche very calmly said, “All things tend towards goodness, this can’t be stopped, whether you believe it or not doesn’t matter.” And as one of the participants said, “I would rather believe that, because the alternative is too depressing.”

We could argue that Buddhism is naïve, that it is optimistic. That’s why the most important thing we can do is test it out for ourselves. Look closely, reflect, experience, what do you see? Robert Thurman called Buddhism “engaged realism.” I like that, but we have to be engaged with reality. We have to be looking and questioning and testing, does this make sense? Does this work as I’m being told it does? Is this teaching true?

The Buddha said there are eight conditions for the arising of wisdom (wisdom being the deep understanding of things as they are). Wisdom does not belong to Buddhism, it is simply the way things work. Buddhism has a particular framework for it, and a way to practice, cultivate, and realize it. But if Buddhism disappeared from the earth, if no one practiced it anymore, the truth of things would still be true.

So, the first of these conditions is to:

1. Study with a teacher, having a sense of respect, affection, and trust toward that teacher. Without these elements, a teacher can’t teach you. You have to give permission, and you have to have a certain amount of faith that this person can guide you—not infallibly—but on a human path of practice and realization without a teacher, we can get arrogant and think we’ve arrived, we can get discouraged and think we’ll never get there. Daido Roshi saw me as a buddha, made me believe I could awaken.

2. The second is asking, having such a teacher or teachers, you must have the willingness to ask about what you don’t yet understand… you know, sometimes people won’t come to face-to-face teaching. Often they say, I don’t have anything to ask and I think, how can that be? There are thousands upon thousands of teachings and commentaries on those teachings. There are the hours and hours of zazen we do every day, every week, every month. There’s your mind, your body, just human consciousness, what is that? You can’t possibly understand it all, so why not ask?

Without asking, how will I know? How will I understand? And really, the most important thing is asking ourselves. That’s the gift we’ve been given, with human consciousness, the ability to reflect and ask.

3. The third condition for wisdom is withdrawal or seclusion. In the sutras, the Buddha describes the states of concentration called jhanas he entered into before his enlightenment. He said:

Quite secluded from sense pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states of mind, [a practitioner] enters and dwells in the first jhana, which is accompanied by applied thought and sustained thought with rapture and happiness born of seclusion.

We do retreats because it is necessary, in order to see clearly, to minimize distractions and, in a sense, to protect ourselves from unwholesome states of mind. To protect ourselves from sense pleasures and distractions. Not as a way to avoid our lives, but as a way to see clearly, so we can, when we get off the cushion, meet our lives wholeheartedly.

The dharma doesn’t need protection, we do—from ourselves, from our confusion and our reactive and often ineffectual habits.

Think of a moment in which you felt threatened and then reactively criticized someone else. You put them down in order to hide your insecurity and to feel better about yourself. It works, doesn’t it?—unless you’re really paying attention, then you’ll detect that feeling of uuuuugh that arises when you do something like that. It’s like looking down and seeing there’s a trail of toilet paper stuck to the back of your pants and you’ve been walking through the hallways with it. And you thought you had fooled everyone.

4. The fourth condition for wisdom is virtue or ethical conduct. When we practice what is wholesome and avoid what is unwholesome, our mind becomes joyful and concentrated, this in turn, leads to wisdom. When we act unskillfully, harming others or ourselves, our minds are agitated, it becomes difficult to even think straight, let alone concentrate. We can certainly compartmentalize, repress, avoid, ignore, but that takes energy—energy that is not available to clearly see so, although in the beginning zazen is very effortful and can therefore be tiring, after a while, it become more effortless, more natural.

5. The fifth condition is learning, remembering, and reflecting on the teachings. It is not enough to just hear a talk or do a retreat, we need to reflect on what we’ve heard, we need to let these teachings permeate our lives. When that happens, they’re right at our fingertips when we need them—which is what we want. What’s the point of learning something if we’re not going to use it, right?

Shugen Roshi often asks us during our study sessions, how would you say this—a dharma point—in your own words? First you’re studying the sutras, liturgy, with the words that have been handed down, at a certain point those words become your words, they become your truth. It’s not my practice over here and my life over there, they are one thing.

6. The sixth condition is energy. We need to be energetic and determined in our effort to free ourselves. We’re dealing with delusion. I remind myself of that when I complain about the long hours, the rigor of this practice, its discipline. So yes, we absolutely have to take care of ourselves and be gentle when we need to be gentle. We also have to be willing to work hard to identify and see through our familiar but unskillful ways of navigating our minds, our emotional states, our world.

Being mindful is not just paying attention, your mind needs to be stable, your body still, otherwise there is too much interference, too much static. It’s not the only way to work with your body and mind, by any means, but it is a very powerful way, a very effective way. So how do you know when you need to stretch yourself, challenge yourself in your practice, aspire to something larger, and when do you need to relax and accept where you are? No one can answer that for you, not even a teacher. Ultimately, each one of us have to be our own guide.

7. The seventh condition is practicing right speech. It’s not engaging in idle talk, and not shunning noble silence at a time when we, as a culture, are talking so much but saying so little. What is right speech? When is silence noble? When is it dangerous?

I am a student of silence, of stillness and silence and the power they bring. Without stillness and deep, abiding silence, we get thrown about by every passing wind, every storm, every cloud.

8. The eighth condition is contemplating the rise and fall of the five aggregates. It is understanding how form, sensation, conception, discrimination, and awareness—essentially what we take as the self—arise, and how they pass. These are the five skandhas that we chanted this morning in the Heart Sutra. The problem is not that we have form and we feel and conceive and discriminate and are aware (how else would we experience anything?) The problem is that we cling to that experience. We identify with it, and try to possess it. A thought, a feeling, becomes “my” thought, becomes “me.” “I am angry,” or, “You made me angry and now I’m angry, so take my anger away and if you won’t, I’ll put it on you.” But understanding that this feeling does not belong to me, is not me, we’re able to watch it rise and fall.

I really don’t like coconut, I have a lot of trouble with it. Form (piece of coconut), sensation (moment it touches my tongue), this is still pure. I don’t yet know what it is. Conception (taste of coconut), discrimination (I don’t like it, action: I move away), awareness or consciousness (puts it all together, I am aware of it), but if I don’t place myself at the center of this experience, if I just experience it, allowing it to rise and fall, where is the conflict? Who creates it?

Now, this may seem kind of technical, this list of conditions but really, this teaching is describing the things that need to be in place in order for us to see more clearly.

I like to call zazen the practice of seeing reality. Seeing things, not as we would like them to be, not as we think they should be, but as they really are. An incredibly powerful practice, a challenging practice. Most importantly, a practice of liberation. But don’t believe me when I say that, test it, try it out for yourself.

Galway Kinnell also said:

Never mind. The self is the least of it. Let our scars fall in love.

I think, ultimately, this is what’s being asked of us—that our scars fall in love with one other. Not our ideal selves, not the selves we will become when we get our act together when our practice is strong according to some ideal we’ve set for ourselves, but now, right now. Our scars and our shadows and our demons and our hidden fears.

First we have to fall in love with them, completely (we have to accept them, respect them). Then we have to have the courage to let others fall in love with them too. Because it’s only in the doing of this that we will reteach ourselves our loveliness. By making our way through the fodder and the slops, the spininess and the wry curliness of our self-doubt and our shame and our self-consciousness, and the sharp shards of our broken hearts… It’s only there that we will reclaim our loveliness.

So don’t wait for another time, another place. There is no such thing. This is it, this is all we have…

And it is enough.

The Eight Conditions for Wisdom, a dharma talk by Zen Buddhist teacher Zuisei Goddard. Audio podcast and transcript available.

Explore further

01 : Saint Francis and the Sow by Galway Kinnell

02 : The Eight Conditions for Wisdom

03 : Engaged Realism by Robert Thurman