Working with Fear

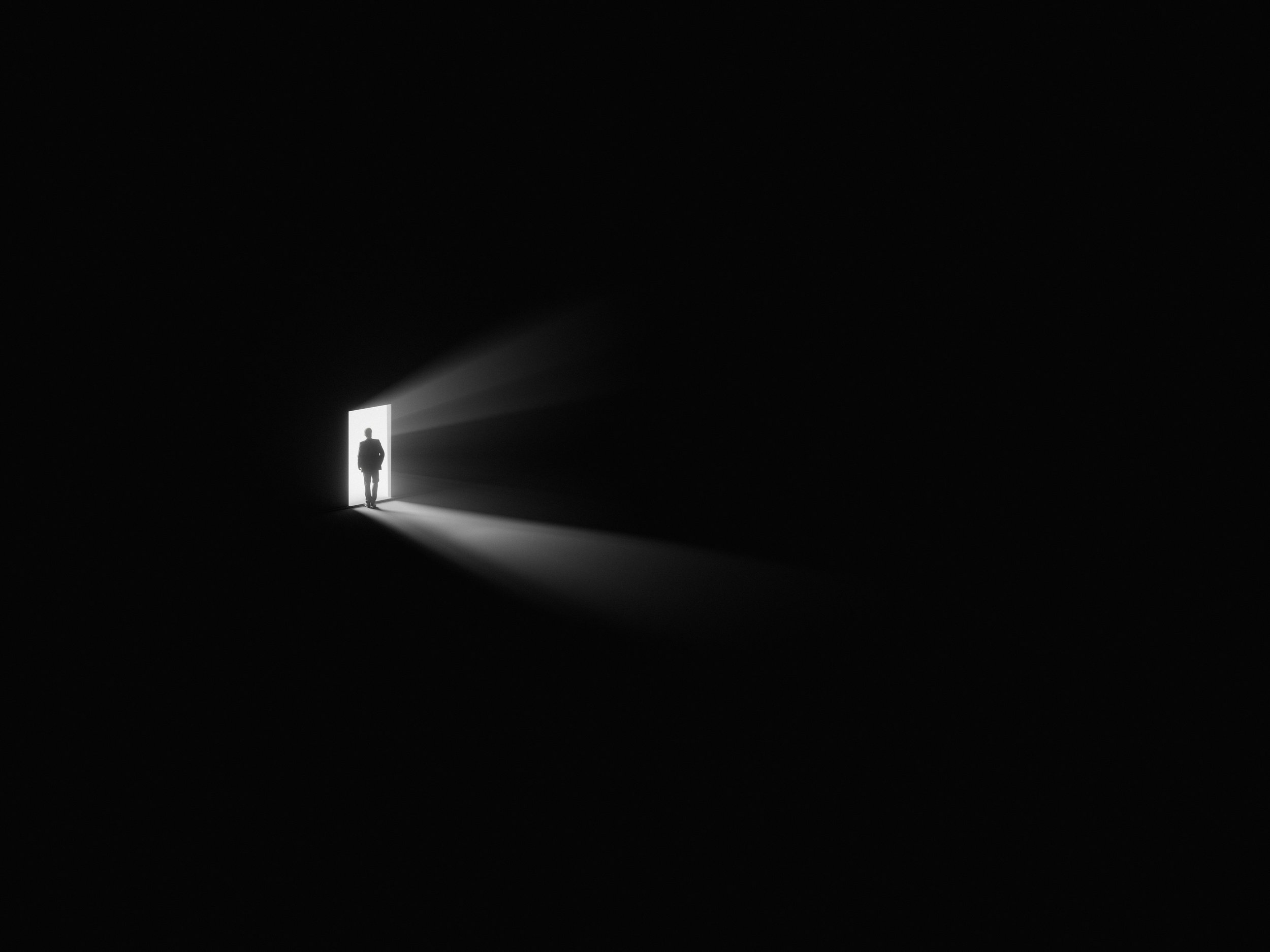

Photo by Viktor Forgacs

I can’t. I won’t. This is the sound of fear in the lead. And a sign to look closer.

In this talk Zuisei returns to the three steps or ways to enter our zazen—failing, falling, and feeling—and studies the fear that often holds us back from fully realizing them. How does practice enable us to stay with our fear—to be both fearful and fearless?

Zuisei reminds us that when we realize that we’re like the sky, vast and boundless, there’s no thought or feeling we cannot face or hold.

This talk includes a short guided meditation.

This talk was given by Zuisei Goddard. See below for transcript.

Transcript

This transcript is based on Zuisei's talk notes and may differ slightly from the final talk.

Working with Fear

I want to start with this quote by the very quotable Pema Chödron: "Fear is the natural reaction to moving closer to the truth." I’m starting with this because I wanted to pick up on a couple of things that I said in my last talk. Something that I didn't say in the steps that I delineated last week: fail, fall, feel—they aren't technically shikantaza. Shikantaza is silent illumination, just sitting with bare awareness. Some contemporary teachers have called it the methodless method of zazen. So, you really are thinking nonthinking. You are sitting without focus, without an object of meditation. This is not an easy practice, by any means. So, implicit in the instruction, think nonthinking, is the question, How? How do you do this when the mind is thinking all the time?

So, I want to give a scaffolding, a way for us to create some sort of structure around a practice that has no structure. Because, though it seems that it would be simple to sit with open awareness, it’s not easy to sit without a goal, without focus, without striving day after day, week after week, year after year, trusting there is nothing that we need to fix, nothing even to realize, fundamentally. Most of us are going to need a little help, a way to enter in order to gradually embody that trust in this practice.

In all honesty, most of us will need something to do during our zazen, however subtle, at least for a while. Otherwise, the danger is that we just drift, here and there, like clouds. Although that is partially the point. As I was reflecting on this, observing my own sitting practice, I came up with these three steps—fail, fall, feel—to try to describe what is necessary to do this kind of sitting.

Those of you who have been listening to my talks know that I have another set of steps to deal with difficult feelings: attend, allow, accept. I used to make fun of what I considered a very American insistence on spelling things out. Creating lists that you can condense into memorable acronyms, posting them on your fridge, printing them on cards, and putting them on your desktop. It always felt a little cheesy, a little self-helpy. But as I untighten with age, hopefully, and with practice, I have begun to see it a little bit differently. Especially as I started reading the Vajrayana teachings and seeing the teachers there are not afraid to spell things out at all, to break things into very manageable, actionable steps. In one way, neither are the sutras. They might not be so focused on alliteration, but they are often saying, this is what you do first, and then this, and then this, and then this. They are not really linear, step by step like that, but they do break things down. Zen has a style of just cutting through, of directly pointing, which is incredibly powerful and effective once you get the hang of it, but to get there, you do need to set the ground. I've been reflecting a lot on my own early days of practice and the many things I had to learn and figure out on my own. It wouldn't have been so bad back then to get a little more explicit explanation.

Now I see the benefit of creating aides to practice. I've done it for many years in my own practice by coming up with my own tools and tricks to inspire myself, to encourage myself, to direct myself when I don't know what's going on by being my own teacher in the solitude of my own zazen.

Every single one of us has to sit down on our cushion with our own mind and work things out for ourselves ultimately. But if there are tools that can help us, then we don't have to start from scratch every time.

Now, even the steps that I delineated: fail, fall and feel, are not that easy to do, actually. It is one thing to say fail, completely, and quite another to do it. I don't like failing at all. I never have. It's taken me not having a choice, not being able to pretend that I can manipulate a situation to come out looking better, and seeing that I can survive what we call failure, what we think is failure, to see that it’s okay. Really, the only thing I can't survive is death, and I'm not supposed to, at least not in this form. Everything else I can work with.

It's not so easy to fall either, which I equated with free-diving in my previous talk. In zazen, we're going deep into our body and mind. Probably the single thing I hear most from students is, “I want to go deeper in my practice, and I don't know how.” Let go. Let go. Let go. Let go of the life jacket, because otherwise you'll just keep floating around. But again, how? Let go of what? What does that mean, to let go? The what is everything, at least while you're doing zazen. We have to let go of everything. But when I heard this, I nodded, sat down, and then held on for dear life because my thoughts seemed too real. They were too compelling and too pressing to release.

It makes me think of a koan between Zhaozhou and a monk named Yanyang. Yanyang asked Zhaozhou, “How is it when nothing comes up?” Zhaozhou said, “Cast it off.” Yanyang said, “When nothing comes up, how can you cast it off?” Zhaozhou said, “Then carry it with you.”

They're talking about emptiness and not holding onto the idea of emptiness, but if you think about it, it also applies to anything we hold onto in our lives. A teacher says, “Let go.” Of your anger, your jealousy, your self-doubt. And the student says, “I can't.” “Okay. Then carry it with you.”

When I was a kid, if I hurt myself and said to my father, “Dad, if I lift my arm, it hurts.” And my father would say, “Well, then don't lift it.” Thanks, Dad. But in a way, it's true. If you can’t let go, then carry it with you. It's okay to carry it with you. But we can also look closely at this I can't. What it's based on is fear. That's really what I wanted to go deeper into tonight.

I want to be free of failing. I really do, but I'm also afraid of what will happen if I truly let myself fail. I want to go deep. I want to fall into myself, into practice, into this vastness that I can't really contain and can't frame. But I'm afraid if I do, then I won't come back to see the light of day. We've talked about this point, this moment, where you're just at the edge of letting go in your zazen, and something happens to keep the self nice and solid. Real.

Afraid of failing and falling, I'm definitely afraid to feel as well, because what if it overwhelms me? Accompanying this fear is also the conviction that if we still feel fear, pain, loneliness, impatience or resistance, then we must be doing something wrong. Surely, enlightened people don't feel these things anymore. Surely they're free of them, right? Otherwise, what's the point of practice? Well, it's certainly not to be numb. It's not to stop feeling. It's to feel, fail and continue, to fall and continue, to feel and continue. So, it's never really about what you've seen or haven't seen or what you can or can't do. It's about continuing step, by step, by step.

We already know that fearlessness doesn't translate into absence of fear. We can say it translates into continuing, into feeling afraid and not letting that stop us from doing what we want to do, what we need to do, and what we aspire to do.

I’ve told this story before of Trungpa Rinpoche. He is with a group of people, and they're crossing a yard. There’s a huge dog straining against his leash, growling and barking as they approach. Everybody is edging away, but at a certain point, the chain breaks, and the dog starts running full-tilt towards them. Everybody freaks out, scatters, and runs away, but Trungpa turns, looks at the dog, and runs straight at it, yelling. The dog is so startled that he stops, turns around, and runs away with his tail between its legs. This is how to meet fear.

For years I've told this story, but with Trungpa facing a bull, and I wonder where I got that from? Trungpa facing a bull across a field. I would really build it up—the bull pawing the ground and everything. I was sure that was the story.

In any case, you move toward rather than away from. The fact is, we don't actually have to be heroic. Being fearless is not always like that. Sometimes heroism is so gentle, so ordinary, that we risk missing it. The moment when your heart starts fluttering and you still take that step. Like deciding you'll do the chant, at the end of the evening on Wednesday night, thinking I can't, I can't, I can't, I won't. What if I make a fool of myself? And you still step forward because you want to be in your life.

There was a woman who was so painfully shy that she never spoke in groups, ever. She was fine with that. Mostly she got through her life, but she got a job where it really started to affect her ability to do her work. She would be in creative meetings, and she was unable to offer her input, even though her supervisors knew she had a lot to offer. At a certain point, she decided she was really going to take the bull by the horns. So, whenever she felt the impulse to say something, she would shoot both hands up in the air. She describes the effect that this had on her. Doing something a little over the top, a little ridiculous, was the nudge she needed to get past her own hesitation. Plus, there was no way that anybody would miss seeing her in the room. This is how she gradually trained herself to speak when she wanted to.

Ultimately, I think being fearless really means being willing to relinquish our need to be in control. It's the moment that we stop paving the world with leather, and instead put leather sandals on our feet. In that famous Shantideva quote, he’s speaking about training and mastering the mind. Instead of trying to control your environment and circumstances—covering the whole world with leather so you can softly step—just put leather sandals on your feet. Master your own mind. Adapt to reality, rather than trying to force and shape it into your own image. This requires a fierce willingness to stay present when you don't want to.

A couple of weeks ago, a number of women got together for a meeting of what we're calling for now Women in Practice. It's a group for people who identify as women to speak about what that experience is like within the context of practice. It was our second meeting, and it was difficult. People had strong views with strong feelings behind them. It was all happening in the moment, and we were all trying to figure out how to navigate one another and the storm. It was a minor storm, but a storm nonetheless. I felt discomfort in my body. I felt the tightening in my stomach and a very strong urge to jump in, fix, and smooth things out. Then I heard another voice in my mind: “Stay, get close.” So I did, or I tried my best to stay and be present in my whole body and my whole mind with what was happening. I did not let my feelings just sweep me away. I didn’t let my fear and my discomfort lead because that would strengthen the habit, so that next time I encountered something difficult, I’d want to run. Staying is breaking that habit.

In zazen, our stillness breaks the habit of moving away when we're in pain, when we're uncomfortable, when we're restless. It’s not discipline for discipline's sake. We're training ourselves to be free in small ways and large ways. Of course, there are situations in which leaving is the best choice, the necessary choice. But a lot of the time we're just reacting. We don't like to be uncomfortable, and we avoid it at all costs. So next time you want to run, try it. Whisper to yourself, stay. See what happens. This is one of the skills we're learning in the Bodhisattva Academy, along with attend, allow, accept, fail, fall, feel, and stay.

I’d like to do something we don't normally do in these talks because I want to give you a practical way to cultivate this ability to stay. I'd like to sit for five minutes. This is the instruction:

Close your eyes. Now, see in your mind’s eye, the sky. Let's say a day sky, blue with a few clouds. For five minutes, sit quietly and be the sky. And when you notice a thought that takes you away from the vast openness that is sky, say to yourself very softly, clouds. That's a cloud passing by. Then, return to being the sky and softly say to yourself, sky.

[five minute meditation]

This being the sky is really what fearlessness is. It's being that open and vast, which we always are. The clouds are also part of this sky. Every thought that stops us, makes us doubt, constricts, and pushes us away, is just a cloud. Just a cloud in all of that space. I think of what Daido Roshi used to say: "Zazen is not meditation. It's not contemplation. It’s not quieting the mind. It’s not focusing the mind. It’s not mindfulness, it's not mindlessness. Zazen is a way of using your mind. It's a way of living your life and doing it with other people." But that's already too much, and he knew that. Zazen is zazen. If we have to call it something, call it, being sky. That is the constant, bewildering paradox of practice. All of these teachings, all of the many hours of learning and practice, all of the sitting on your butt on that cushion, failing and falling. All are in order to do what you've always done, in order to be who you have always been and to do it naturally and effortlessly. You do need to put in effort. Then, when life challenges and stretches you, when it asks that you do something that scares you, you can be there, fully.

Working with Fear, a dharma talk by Zen Buddhist teacher Zuisei Goddard. Audio podcast, video, and transcript available.

Explore further

01 : When Things Fall Apart, Excerpt by Pema Chödrön

02 : Shikantaza by Vanessa Zuisei Goddard

03 : The Way of the Bodhisattva by Shantideva, translated by Padmakara Translation Group